Review Essay

A Movement Memoir with Broader Implications

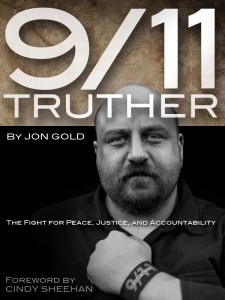

Jon Gold, 9/11 Truther: The Fight for Peace, Justice and Accountability.

Jon Gold, 9/11 Truther: The Fight for Peace, Justice and Accountability.

Foreword by Cindy Sheehan. ePublishPartners.com, 2012.

9/11 Truther is a significant book because it both renders leading personalities in the movement and also, at its best, displays wide, well researched knowledge of many key issues. By March, 2012, this new book had risen to #15 in Practical Politics at Amazon.

As one of the first 9/11 memoirs, 9/11 Truther takes readers into the life of an activist, now 40, who’s been an important player on the East Coast and in the blogosphere. Jon Gold went to Hebrew school and took his Bar Mitzvah. Later, as he moved into “calling out” people he believed were hurting the movement with their wild speculations, Gold encountered vicious anti-Semitism. Consequences included high blood pressure, chronic depression, and, later, panic attacks (pp. 112-115). The book does not, however, explore broader questions of anti-Semitism in the 9/11 movement.

The first few dozen pages recount how Gold got into drugs, attempted suicide, and joined narcotics anonymous. Though the first 55 pages or so could strike readers as largely, perhaps overly autobiographical, they do capture key moments in the movement.

Unlike some “truthers,” Gold doesn’t claim to have “woken up” right away, almost before the smoke had cleared. After 9/11, he worked as a web developer and did the “patriotic” things, placing a small American flag on the company website.

Gold’s Entry into the Truth Movement

By 2004, however, questions were piling up, eroding Gold’s belief in the Official Story. When he watched Kyle Hence of Citizens Watch question the 9/11 Commission findings on C-SPAN, he felt immediate resonance: “They were asking many of the same questions I had been asking.” In an intense moment of self-confrontation, he felt “abused by the media and by the government. I [had] openly advocated killing people because of the lies I was told.”

The next year, led by 9/11 widows Lorie Van Auken, Patty Cazzara, Mindy Kleinberg and Monica Gabrielle, a group of family members issued a statement questioning the “entire veracity of the 9/11 Report.” Along with bereaved father Bob McIlvaine, they mounted a cogent challenge to the corporate media which had uncritically accepted the Report. But the news media continued to afford scant coverage to their challenge. Two years later, Gold attended a preview of “Press for Truth,” which he believes is the “most important documentary of our age,” but which received almost no media coverage at the time. Nor has it received much since.

Inspired by Jenna Orkin, an outspoken health-issue activist, and also moved by compassion, Gold became especially concerned with the health problems caused by the environmental conditions in Lower Manhattan, especially on “the Pile” (pp. 49ff). He raised $3,000 for first responders, some of whom were becoming seriously ill by this time. Gold received an award as Honorary Director of the FealGood Foundation, and this, he feels, was “the greatest moment of my life.” At a benefit for first responders on the sixth anniversary of the attacks, Gold introduced injured responder John Feal and later met actor Daniel Sunjata, star of the TV show “Rescue Me.”

Concerns over Movement Ethics and Tactics

By 2006, Gold had come under the influence of Paul Thompson and his amazing research project, historycommons.org. Because of Gold’s affinity for this approach and his closeness to the families of victims, Gold became concerned that “too much emphasis was being placed on the physical aspects of 9/11.” (This extended the perspectives of Michael Ruppert who, several years before, had rejected the utility of physical evidence). In contrast, Gold was impressed with the “Eleventh Day”-of-the-month street actions popularized by Cosmos, a Bay Area activist. Although Gold believes that “no better action [has been] devised for this cause” (p. 55), he doesn’t say why.

In 2008, increasingly concerned that the corporate media were refusing to cover 9/11 critique, Gold made a series of ten videos about different 9/11 family members. (These are available at 911Truth.org). Throughout his subsequent years as a 9/11 activist, Gold has made extensive use of his talents as a designer. Though he claims “I’m a regular, everyday person who’s paying attention and trying to make a difference,” he’s obviously a very bright fellow who’s devoted many years to learning in service of the cause.

Also in 2008, Gold, Nicholas Levis and 9/11 family member Donna Marsh O’Connor brought forth a “Declaration of Standards and Strategies for 9/11 Truth” (pp. 69ff). They called for “awareness of public perception and the need for strategic and responsible promotion and presentation,” a “commitment to build credibility and constructive alliances with the peace movement” and “adherence to the scientific method and journalistic standards, with a focus on facts, substance, and sources.”

Not surprisingly, Gold expressed his concerns about extravagant claims, such as Judy Wood’s belief that beams from space had brought down the Towers, or conspiracy mongering, which he felt characterized the statements of Alex Jones and WeAreChange. Somewhat more surprisingly, by mid-decade Gold had concluded that belief in controlled demolition was becoming a kind of cultish litmus test (p. 105). Gold cautioned not only against “speculative theories” but also against “disruptive behavior” (within the movement). He also called for “self critique”; in a prophetic call to action, he pointed out “we can’t sit on websites arguing whose theory is right or wrong until this issue disappears into the ether” (p. 88).

Though the Declaration’s calls were much needed, most of them went unheeded. Sadly, some “fringe” elements saw them as attempts to silence them, so the injunctions themselves became divisive. Thus Gold seems to represent a large class of 9/11 activists who have insisted on grounded facts and logical arguments, only to be marginalized by the news media and pummeled by those favoring “flights of fancy.” He continues this internal critique today, often challenging the selection of speakers prone to sensationalism.

A Growing Acrimony and Aversion to Science

Since 2011, Gold has also indulged his disdain for scientific analysis of the buildings, even to the point of repeatedly blaming Richard Gage for the decline of the truth movement (TruthAction.org: 6/02/11, 6/18/11, 10/19/11, 2/21/12). At their worst, these attacks have struck a tone that’s not only vulgar but full of self-pity: “I’ve only wasted a decade of my life on this, only to have it thrown under a bus by ASSHOLES… Given up my life, my friends, my health . . . for this” (see: truthaction.org). Sure, especially when those posting can hide behind code names, internet “chats” often become histrionic, but…

The tirades against Richard Gage are not only bitter and vulgar; they’re usually false. Rather than sinking the movement, Gage’s Architects and Engineers have demonstrably helped to keep it afloat. If AE has a problem, it’s probably not that it’s excessively scientific, but that it’s sometimes not sufficiently so. While Gold once represented a conscientious commitment to truth telling, in the past year he’s seemingly moved toward irrational, disruptive personal attacks.

Connecting with Sheehan and the Peace Movement

Again, it wasn’t always this way. Earlier, Gold had made significant efforts to work with the peace movement. In 2009, he met Cindy Sheehan and became involved with “Peace of the Action,” based on “putting bodies on the gears of the machine to stop this empire.” His work with Sheehan continued into 2010, when her efforts evolved into Camp OUT NOW at the Washington Monument and a demonstration using false coffins (p. 80).

Exhaustion and disillusionment were becoming evident. The Sizzlin’ Summer Protests, an extension of the Camp, were “such a disappointment to us when no one showed up.” In 2009 and 2010, Gold also worked with NYCCAN (New York City Coalition for Accountability Now); when, later that year, this initiative also failed, it “was the ‘last straw’ for me” (p.74).

Much more recently, Gold seems interested in revisiting questions of the movement’s rhetoric and persona. In her Foreword, Sheehan recalls that

The most prevalent of these people who bombarded me, though, were the 9/11 ‘Truthers.’ I was harassed all over the world by them and I swear if one more person asked me if I saw ‘Loose Change’ I was going to forget my pacifism and punch him (it was always a him) in the face. The sad thing about this harassment was that I never believed the so-called official story of 9/11 and would have tended to be an ally to these people, but they were so rude and pushy. And, I didn’t feel that I had the time or the inclination to wade through the stacks of information that they tried to force on me …. I left a lot of that material in cabs or garbage cans.

The implication is that Jon Gold was one of the few “truthers” who favorably impressed Sheehan—and that he, perhaps more than any other individual, helped to bring her into the truth movement. Readers might like to know how he succeeded after so many others had failed.

Gold’s Orientation to Real-Life Issues

When Gold urged that we let “the facts speak for themselves” (pp. 131ff), he typically means grounded journalistic research such as that done by Paul Thompson and others at historycommons.org. Gold clearly favors foreknowledge arguments pointing to government involvement; thus we’re not surprised when he links to a network story (MSNBC 9/9/01) revealing that the Bush administration was planning an attack on Afghanistan. Gold also provides solid information on the CIA’s Office of Technical Services, which made an Osama bin Laden propaganda video. The book also contributes valuable research on the suspicious spike in insider trading just before the attacks (pp. 157, 160-62) and on the profits made on War on Terror (pp. 176-77).

Though Gold is also well versed on Philip Shenon’s The Commisson, he does not provide much critique of that book. His strongest affinity is with whistleblowers, particularly those associated with families of the victims who were ignored by the Commission. His interest in foreknowledge also leads him to retell the story of the Israelis seen dancing for joy on the roof of an Urban Moving Systems van (pp. 147ff). The van’s location, in Liberty State Park just across the Hudson from the stricken Towers, was also telling. Five Israelis were arrested but soon released and allowed to leave the country. Just three days later, on 9/14/01, the owner of the company fled to Israel. The fact that Gold is Jewish should counter potential suspicion of anti-Semitism when he discusses likely Israeli/Mossad involvement. It has not, however, kept him from being slandered as a government agent.

The final section of 9/11 Truther, Random Articles from Over the Years, is sometimes repetitive and less compelling. In addition, the book would be a better if it had an index. Overall, though, it’s an important retrospective that will encourage many activists to introspect on where they’ve been and where they need to go.

Paul W. Rea, PhD, is the author of Mounting Evidence (2011). More on movement players, plus a very complete bibliography on 9/11, are available at mountingevidence.org